THE BAPTISED COMMUNITY

What does it mean to be part of the baptised community? The first and dramatic truth is that you are a dead person.

Many people have multiple identities in the modern world. It might be relatively simple: that you are English, British and European. Yet for some it is more complicated, as for the man about to be sworn in as the 44th President of the United States, having connections to Kenya and Indonesia as well as America. Despite the existence of overlapping identities today, one identity is usually stronger than the others. Yet even this one dominant identity can change. Thirty years ago, if you had asked the nationality of someone from England they would likely have said British. Now there are many who would say English instead.

This narrowing of identity is a reversal of what is happening in the Muslim world. Between the 1950s and the 1970s, Arab nationalism, championed by Abdul Nasser, followed a very modern and secular path where the nation has priority. Yet between the 1980s and today, this has begun to be replaced by a greater sense of the worldwide Muslim community, the umma.

This was always the goal of Islam – one of Muhammad’s greatest achievements was the way he enabled one new Muslim identity to overcome the historic tribal divisions in Arabia. This recovered sense of the one worldwide Muslim community is, ironically, more neo-conservative than the outgoing American administration.

All this contrasts powerfully with Christian identity today. If you ask most Christians in Britain what their primary identity is, they would say British. I am quite sure this would be replicated in the United States, France, Germany and other countries of the west. We judge others by their nationality first. We say for instance that he is a German Christian or she is a Brazilian Christian or he is an Indian Christian. It would feel clumsy to say: he is a Christian German or she is a Christian Brazilian and so on. Why is this so?

Inevitably we are shaped by politics and culture. Nationalism has been the dominant force for several centuries and our education, upbringing and media have given us this way of looking at the world. The other big factor in the west is individualism. People resist belonging to bigger communities because their social lives are smaller and self-selecting.

All this is a pity, indeed it may be something of a failing on our part. At the origin of Christianity is one primary loyalty: to Jesus Christ. This is evident in that first confession: ‘Jesus is Lord’. This may seem unexceptional to us, reciting the creeds week by week in our churches, yet for the first Christians it was a sign that their allegiance to Christ came before their enforced loyalty to Caesar. You could be thrown to the lions for saying: ‘Jesus is Lord’ in the Roman world. It was a direct challenge to the temporal power. In parts of the world today, Christians are still vulnerable because of this allegiance. The Muslim world is largely intolerant of Christian expression; China continues to repress faith; while North Korea is a terrifying place to be a Christian.

The churches in such countries belong to us, and we to them. These people are our brothers and sisters and they are maltreated for believing what we believe. There has always been a temptation to turn away from our connections to such people because of the stench of disrepute that imprisonment and troublemaking carries for people in ordered societies like ours. It has always been so. ‘Remember my chains!’ St. Paul requested of the Colossians. He knew how easy it was to turn away.

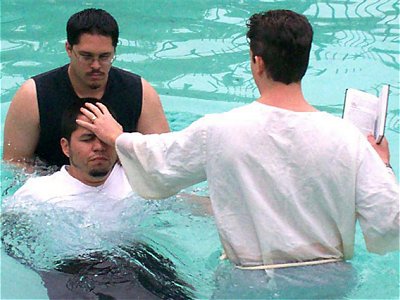

At this time of year (January) many churches recall the baptism of Christ. As John baptised his cousin so we are baptised into Christ. This is both a spiritual and a relational truth and the distinctive sign of belonging to the worldwide Church. We are the baptised community. This point of entry into the faith isn’t one that people readily identify with, despite its importance. Perhaps some are vague about it because they were baptised as babies. There is no memory, only a worn certificate. To reinforce a change in life, a response of the heart is best connected to an external ritual or event. In the Church of England we have the rite of confirmation. I have watched this be a moving declaration of personal faith for many people, yet it lacks the dramatic impact of adult baptism by full immersion which Jesus made and which sometimes precedes confirmation.

So what does it mean to be part of the baptised community? The first and rather stunning truth is that we are dead people. This sounds like a line out of the Godfather (the film that is, not the bloke who makes promises at an infant baptism). It sounds rather like a mafia curse on an informant who must now live in perpetual fear of his life. But for us it is a source of joy. Our old self has been put to death on the cross. ‘I have been crucified with Christ’ says St. Paul. Christ’s death was our death – a death to an old way of life lived away from God. And it is symbolised in baptism most effectively by full immersion of the person into water – like passing through the grave and up into a new life.

Like Jesus himself we are much more than dead people – in fact we are more alive than ever before. If we have died with him, we must also rise from the dead with him. If St. Paul began his sentence to the Galatians with the words ‘I have been crucified with Christ’, he continues ‘and it is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me’. This is the resurrection life his followers share in. And he concludes ‘and the life I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me’. Ours is a ransomed life. We are not our own. We belong to God. This is dramatic, uncompromising testimony. To be a Christian is to be possessed by someone else. The Gospels say that when Jesus was baptised, God’s Spirit descended on him and a new way of life began.

Many Christians struggle to identify with this transformation wrought by baptism. St. Paul could see this and the nature of his response is worth holding on to. You could reasonably summarise his theology by saying this:

Look, he says, don’t strive to make it true. It is true. You are dead – and now you are alive in a new way. Before you start to strive again to earn your standing with God, stop and see what he has done in you without you having to lift a finger. The more you cling to this new identity, the more you will be changed by it. It is true, and the more you live as if it is true, the more real is will become to you. And you are not alone as you embrace this new identity, for you are joining countless other people who have made this journey and you in turn will be joined by many more.

Baptism into Christ should transcend every other way we describe ourselves in life – including where we come from, because where we come from is much less important than where we are going to.

POPULAR ARTICLES

Obama's Covert Wars

The use of drones is going to change warfare out of all recognition in the next decades.

Through A Glass Starkly

Images of traumatic incidents caught on mobile phone can be put to remarkable effect.

What Are British Values?

Is there a British identity and if so, what has shaped the values and institutions that form it?